What a year. What an awful year 2020 has been, and 2021 has been no picnic so far, either. Amid this terrible time, it's basically been a whole year since I've posted in this blog -- since last Passover, really. So now here we are, experiencing the second pandemic Passover (celebrating surviving a plague while surviving a plague -- you can't make this stuff up!) And after a year of home cooking, by necessity, day and night, week after week, I have come to focus on the minutiae. There is little joy to be found in the big-picture, the large-scale suffering, so I've trained myself to find joy in the small and the quotidian. I derive happiness from the family of deer visiting our back yard most Friday afternoons, as if keeping sabbath among our evergreen bushes. I breathe a sigh of relief when our mounds of recycling are picked up every other Thursday. It's finding the calm that comes as I drift off to sleep cradling my baby boy on a stormy afternoon, the sound of wind and rain drumming on the window. And it is enjoying the culinary minutiae as well: the smell of garlicky cannellini beans stewing on the stove, the anticipation of waiting for a loaf of sourdough to rise, the sensory pleasure of digging into some messy smoked BBQ ribs. And sometimes above all, I derive the most pleasure from simply eating a favorite fruit or vegetable in its seasonal glory: the turgid raspberry that stains my fingers, the deep earthiness of a roasted beet used to scoop up some fresh chevre, a slice of eggplant fried to perfection. Included in this group of favorite foods is a vegetable that happens to be in season now and through the spring: the Jerusalem artichoke.

Now, I love a good artichoke. The carciofo, in Italian, is the symbol of Rome, and no city does a vegetable (a thistle, really) justice like the romani di Roma. But my love for the "OG" artichoke may be eclipsed by its sort-of cousin, the Jerusalem artichoke, also known as the sunchoke. It's got many monikers, really -- the Canada potato, the French potato, and most melodic of all, the topinambur (in Italian and various other European languages). So let's begin at the beginning.

First, for the etymology:

The Jerusalem artichoke has nothing to do with the city of Jerusalem, and is not technically an artichoke, though they are distantly related as both are members of the daisy family, and the genus Helianthus. The Jerusalem artichoke's taste is sweet and earthy, much like an artichoke. But the origin of "Jerusalem" is still uncertain. Italian settlers in the U.S called the plant "girasole", their word for sunflower, which translates roughly to "turns towards the sun", since this is exactly what these flowers do. Over time, the word girasole in southern Italian dialect sounds a lot like "Jerusalem" and therefore English speakers may have corrupted the term "girasole artichoke" into its current day moniker. Another theory for the name is that the Puritans who came to the New World considered America the "New Jerusalem" and the plant they found growing there was named after this place. The plant had various other names as well, including lambchoke and sunchoke -- which is another name by which is it known today, created in the 1960s by a produce wholesaler who was trying to revive the tuber's appeal. It looks a lot like ginger root, but its skin is more translucent and slightly more golden in color.

And then, the history:

The Jerusalem artichoke had been cultivated by Native Americans long before Europeans landed on American soil. Apparently, Lewis and Clark ate Jerusalem artichokes, prepared by a Native American woman in what is now North Dakota. It was fairly common in the U.S. and the plant really proliferated in both the Americas and Europe, and grew so easily that it was principally used as animal feed in England and France. The French in particular had a soft spot for the vegetable, which reached its peak popularity at the end of the 19th century. But by the time of the second World War, the Jerusalem artichoke (along with the rutabaga) had become associated with the deprivation of the war years and the Nazi occupation, since they'd become a staple of the French diet thanks to rationing and the paucity of other traditional foods. Once the war was over, they returned to their previous purpose as animal feed. It wouldn't be until the 21st century that the Jerusalem artichoke would find favor again with top chefs, winding up on countless tasting menus in Michelin starred dining rooms.

The nutritional value:

Potassium, iron, fiber, niacin, thiamine, phosphorus, and copper are all nutrients found in abundance in the Jerusalem artichoke. The tuber also contains inulin, a form of soluble fiber that cannot be broken down by our digestive system. It's metabolized, instead, by bacteria in the colon, thereby balancing blood sugar. Inulin also stimulates the growth of bifidobacteria ("good bacteria") and fights harmful bacteria, making the Jerusalem artichoke one of the best food sources on earth for prebiotics. It's also high in soluble fiber, which may help lower total blood cholesterol levels by lowering "bad" cholesterol (or "LDLs"). And finally, the sunchoke is high in potassium and low in sodium, which may aid in the reduction of blood pressure and inflammation. The only negative by-product of all of this healthfulness is that consuming Jerusalem artichokes can cause some serious gas. Forewarned, as they say, is forearmed.

And finally, enjoying the Jerusalem artichoke:

Beyond all of the health benefits of the tuber, and its interesting history, there is the matter of taste: the Jerusalem artichoke is delicious. And versatile.

When treated as a tuber, the sunchoke makes for a wonderful puree and a more healthful alternative to the carb-heavy potato. Thinned with broth or water or milk, it makes an amazing soup, and can be made into a sauce in this way as well. The Jerusalem artichoke can be oven roasted and served as any root vegetable, and also alongside other roasted vegetables in a medley. Finishing a roasted sunchoke on the grill also brings out its sugars and caramelizes the outside of the artichoke. Few finishing touches are as tasty as a Jerusalem artichoke that's been thinly sliced and fried in a top-quality oil. Once fried, they can be a crispy topping (as in the photo, with tuna tartare), an accompaniment to proteins or other vegetables, or as the star in an appetizer in its own right.

One lovely way to prepare Jerusalem artichokes for spring is in a rich and vegetal risotto. Here, I've prepared a classic risotto with the addition of a sunchoke puree stirred into the risotto as it cooks. It's topped with sliced fried crispy Jerusalem artichokes, and flavored with sumac, red onion, lemon zest and juice, and fresh mint -- all flavors redolent of dishes you'd find in the city of Jerusalem, and a way to pay tribute to the name of the tuber itself. It's an Italian dish with an Israeli flavor profile.

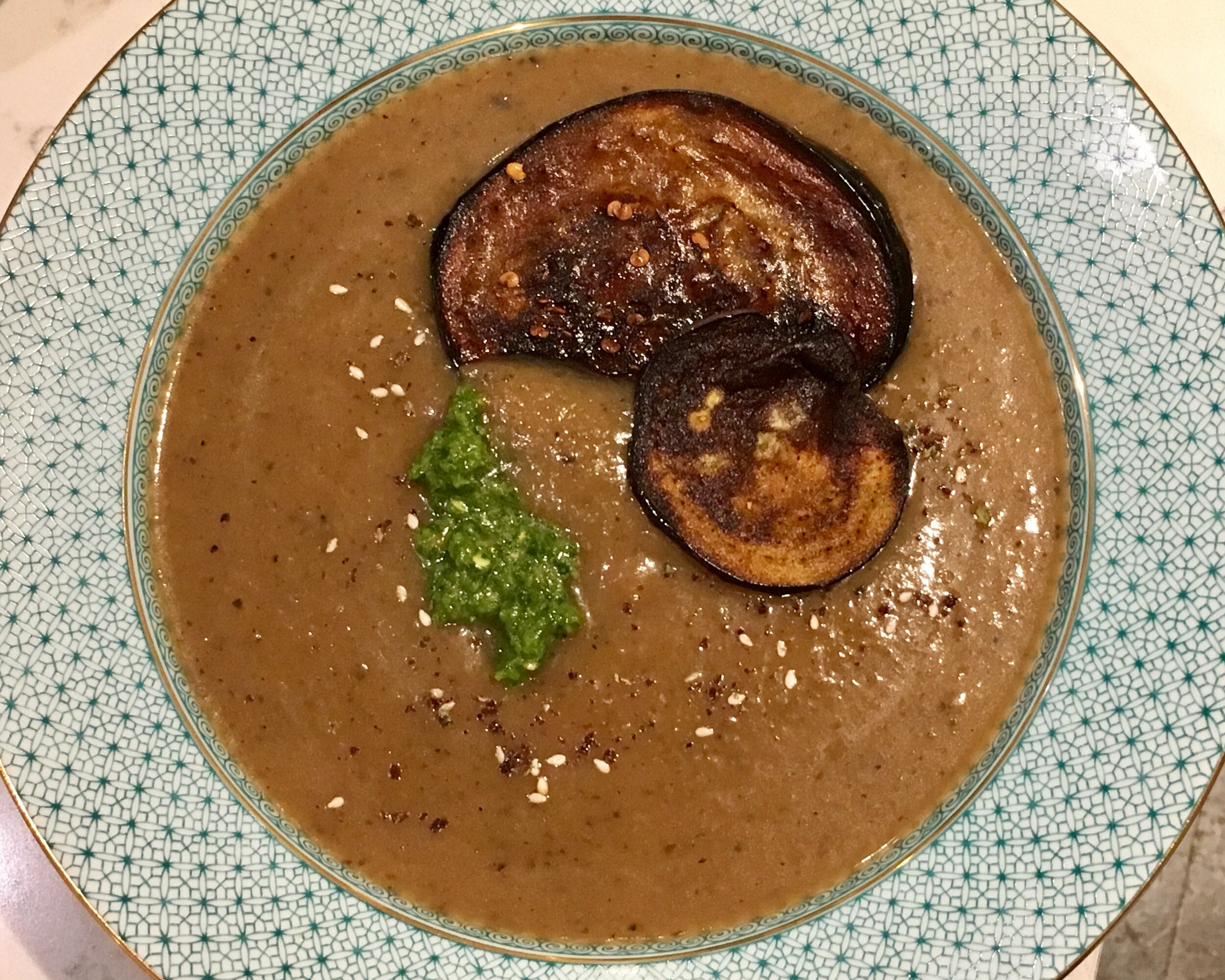

Another great way to enjoy the tuber is in this delicious roasted Jerusalem artichoke soup. It's a multi-step process to concentrate the flavor through oven roasting, but beyond that it couldn't be simpler to prep. Just spread out the cleaned Jerusalem artichokes on a lined baking sheet, toss with olive oil and salt, and oven roast at 375 until they're caramelized and soft in the middle, about 45 minutes to an hour. Once cooled slightly, puree in a Vitamix/blender or food processor with some tasty vegetable broth and a glug of extra-virgin olive oil until you get the consistency you want. Season with salt and pepper, and any other spices you might enjoy. The version I made here is seasoned with roasted garlic (roasted alongside the Jerusalem artichokes) and finished with a bit of fresh lemon juice and zest, and za'atar. I fried eggplant slices and served them atop the soup, with a bit of pistachio pesto as well. This has been a winner for both Passover Seders and everyday eating. It takes me to Israel and the Mediterranean in general, and it's a really healthy way to reset your gut bacteria while satisfying your belly.

As we say during the Seder...Next year in Jerusalem (artichoke)! Enjoy, and Happy Passover, Happy Easter, and Happy Spring, everybody!